In this section you can find out more about Horncastle's Roman heritage. People have lived in what is now Horncastle since at least the Neolithic but it was not until the late Iron Age that something we would think of as a town or village developed.

This was in the higher area around the Stanhope Hall and Boston Road overlooking the meadows of the River Bain. This settlement developed into a Roman Town, which by the third century included houses with stone buildings and painted wall plaster.

In the late third or early fourth century the Romans built a fortification at Horncastle in the angle between the Rivers Bain and Waring. You can find out more about this and the town's Roman history in the sections below.

How might Horncastle's Roman wall have looked?

This video takes you on a journey from the section of wall at the library with a reconstruction of the Roman walls, and the Anglo-Saxon town that later grew up inside.

Horncastle's Roman Walls had been on the 'Heritage At Risk Register' since the first one was compiled by English Heritage back in 1998. The Society tried to draw attention to them for many years. Then in 2012 a new campaign began with Ben Robinson from English Heritage (now Historic England) visiting the town to convene a meeting about what could be done. Many years of work followed, led by Sheila Jonkers and Mary Silverton.

Horncastle's Roman Walls had been on the 'Heritage At Risk Register' since the first one was compiled by English Heritage back in 1998. The Society tried to draw attention to them for many years. Then in 2012 a new campaign began with Ben Robinson from English Heritage (now Historic England) visiting the town to convene a meeting about what could be done. Many years of work followed, led by Sheila Jonkers and Mary Silverton.

The Society worked in partnership with the Horncastle & District Community Association who have responsibility for the wall where it forms the boundary for the Community Centre, including the wall beneath the Community Centre itself and and at St Mary's Square.

In 2018 a detailed specialist survey was carried out by Dr David Watt studying the wall's condition and estimated the costs of the works required to save it. This complex and specialist work is estimated to cost c.£100,000.

Following this we helped lead a successful fundraising campaign to secure a major grant from Historic England, and match funding from the Pilgrim Trust, Horncastle Town Council, East Lindsey District Council's Councillors Community Grants, The Leche Trust, Tesco Bags of Help, the Medlock Trust, the Michael Cornish Charitable Trust. We also delighted to receive over 100 public donations to our Sponsor a Stone appeal.

Then in March 2021 after some delays caused by the pandemic work finally started on site to conserve the wall for future generations. This was carried out by experts from Cliveden Conservation and overseen by our lead advisor Dr David Watt. Most of the work was completed by summer 2021, although some minor tasks will be finished in the autumn.

Find out more about the work to repair the wall in these videos

This video announced the start of work in March 2021.

This video highlights some of the finds made during work the repair the wall. From Roman oysters shells to medieval pottery and Victorian china, they tell the story of this part of Horncastle over the centuries.

This video presented by Mark Hawcroft from Cliveden Conservation shows the complex process of replicating the Roman style lime mortar needed to repair the wall.

This video gives a behind the scenes look at how an team of expert conservators are repairing Horncastle's Roman wall.

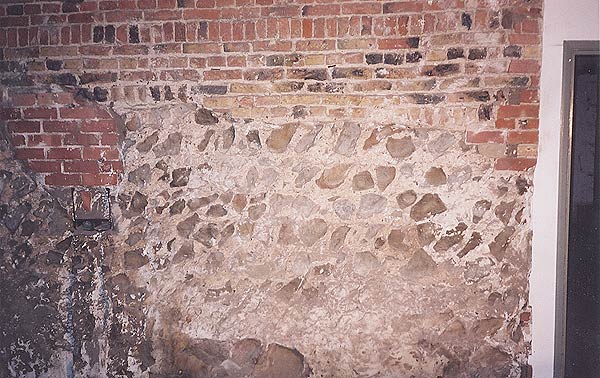

The best preserved sections of the Roman wall can be seen within Horncastle Library where the wall is displayed as a major feature within the building.

Our few lengths of Roman Wall are all that remains of a substantial 3rd or 4th century Roman Fort that enclosed about 5 acres in the centre of Horncastle.

In 1724 William Stukeley described the fort wall as being 3 to 4 yards high and 4 yards thick with square towers in each corner and gates in the middle of 3 sides.

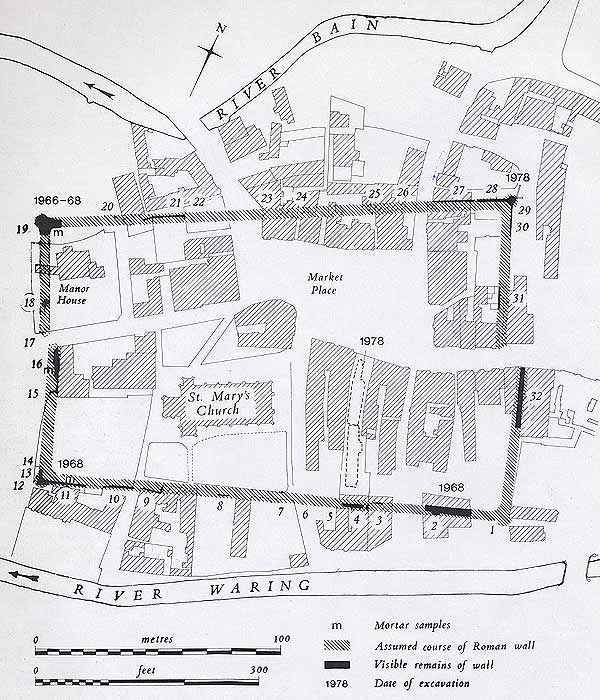

The position of the fort is illustrated below by Mick Clark and appeared in "Roman Horncastle" by Naomi Field and Henry Hurst, published by the Society of Lincolnshire History and Archaeology (SLHA) in 1984. Reproduced with the kind permission of Naomi Field and the SLHA.

The "visible remains of wall" on the diagram includes lengths that are either part of private buildings or on private land, and therefore not accessible. The public can view the wall at no. 2 in the library, no. 16 at the end of Manor House Street or the north east corner near Somerfields.

Horncastle has been recognised as a Roman walled town since at least 1722 when Stukeley first made his map of the town showing the Roman walls. Discoveries made over the last 30 years have changed our view of the site.

Roman Horncastle is now known to have had two main elements of settlement, firstly the walled enclosure of about 5 acres at the junction of the two rivers Bain and Waring, and secondly an unwalled settlement covering up to 135 acres situated on a higher gravel terrace with its centre located around the town hall area.

Coin finds from the unwalled area show that it was the earliest settlement dating from the 1st century, however evidence of earlier occupation (Iron Age) has also been found, possibly indicating a smooth transition during the occupation. The walled circuit has been shown to be a 3rd or 4th century military construction with no evidence of earlier settlement.

Various theories have been suggested to explain why a military fort needed to be built at Horncastle. However it is likely that the site was in closer contact with the sea than it is now - this would give it a strategic defensive position with similarities with other coastal fortifications.

The walls are constructed from local Spilsby sandstone quarried from Holbeck Manor 6km East of Horncastle. Both the East and West walls do not have walls that meet in the centre, indicating a rare type of gate where the walls overlap possibly protected by towers.

A discovery of further interesting Roman relics of another kind was made in 1896. The owner of a garden near Queen Street, in the south-eastern part of the town, was digging up an apple tree when he came across a fine bed of gravel.

Continuing the digging, in order to find the thickness of this deposit, his spade struck against a hard substance, which proved to be a lead coffin. After this had been examined by others invited to inspect it, without any satisfactory result, the present writer was requested to conduct further investigation.

The coffin was found to be 5-ft. 2-in. in length, containing the skeleton, rather shorter, of a female. A few days later a second coffin was found, lying parallel to the first, 5-ft. 7-in. in length, the bones of the skeleton within being larger and evidently those of a male. Subsequently fragments of decayed wood and long iron nails and clamps were found, showing that the leaden coffins had originally been enclosed in wooden cases. Both these coffins lay east and west.

A description was sent to a well-known antiquarian, the late Mr. John Bellows of Gloucester, and he stated that if the lead had an admixture of tin they were Roman, if no tin then they were post-Roman. The lead was afterwards analysed by Professor Church, of Kew, and by the analytical chemist of Messrs. Kynoch & Co., of Birmingham, with the result that there was found to be a percentage of 1.65 of tin to 97.08 of lead and 1.3 of oxygen, "the metal slightly oxidised."

It was thus proved that the coffins were those of Romans, their "orientation" implying that they were Christian.

It should be added that three similar coffins were found in the year 1872, when the foundations were being laid of the New Jerusalem Chapel in Croft Street, within some 100 yards of the two already described; and further, as confirmatory of their being Roman, a lead coffin was also found in the churchyard of Baumber, on the restoration of the church there in 1892, this being close to the Roman road (already mentioned) between the old Roman stations Banovallum and Lindum.

Lead coffins have also been found in the Roman cemeteries at Colchester, York, and at other places.

More ancient lead coffins

Two ancient lead coffins, one containing a male skeleton and the other a female skeleton, both believed to be Roman, are discovered by workmen digging in a market garden field near Queen Street. One of the coffins is transferred to a private museum in Manchester and the other is held by W. K. Mortonís for safekeeping.

Following these discoveries the local historian, the Rev J. Conway Walter, publishes a letter in which he gives details of earlier similar finds in Horncastle and describes early burial procedures. He also instigates an analysis of the lead to determine the tin content from which he concludes that the coffins are indeed Roman, as the lead contains tin.